Arts & Culture

For two centuries, explorers have searched for the wreckage of the world famous Georgia-based vessel

By Guy Martin

March 21, 2023

By last September 30, Hurricane Ian had done its worst in Cuba, Florida, and the Carolinas, and was slowly waltzing up the Eastern Seaboard. As the largely fizzled-out storm shuffled offstage, Ian did manage to kick up gusts and rough water, and some remnants lollygagged off New York for days. It was then that a Fire Island National Seashore ranger noticed that the storm had tossed a heavy, thirteen-square-foot chunk of obviously antique flotsam onto the barrier island, not far from the landmark 1858 Fire Island Lighthouse.

But this wasn’t just any bit of sea junk. The timber was substantial and well-milled, with one or two internal pieces adroitly shaved down to adapt to the curvature of a boat’s hull, or to that of a piece of deck. Also remarkable were the substantial trenails, or wooden dowels, meant to swell in their sockets to hold the timbers tight as they were wetted. The cut (rather than forged) iron spikes in the flotsam dated the piece to a boat built around 1820.

And that’s when the lighthouse and NPS officials knew that Ian had thrown them something special. Maritime experts and academics across the United States now eagerly await the results of further analysis of the deceptively ignoble piece of flotsam—could it truly be, they wonder, a piece of the renowned SS Savannah?

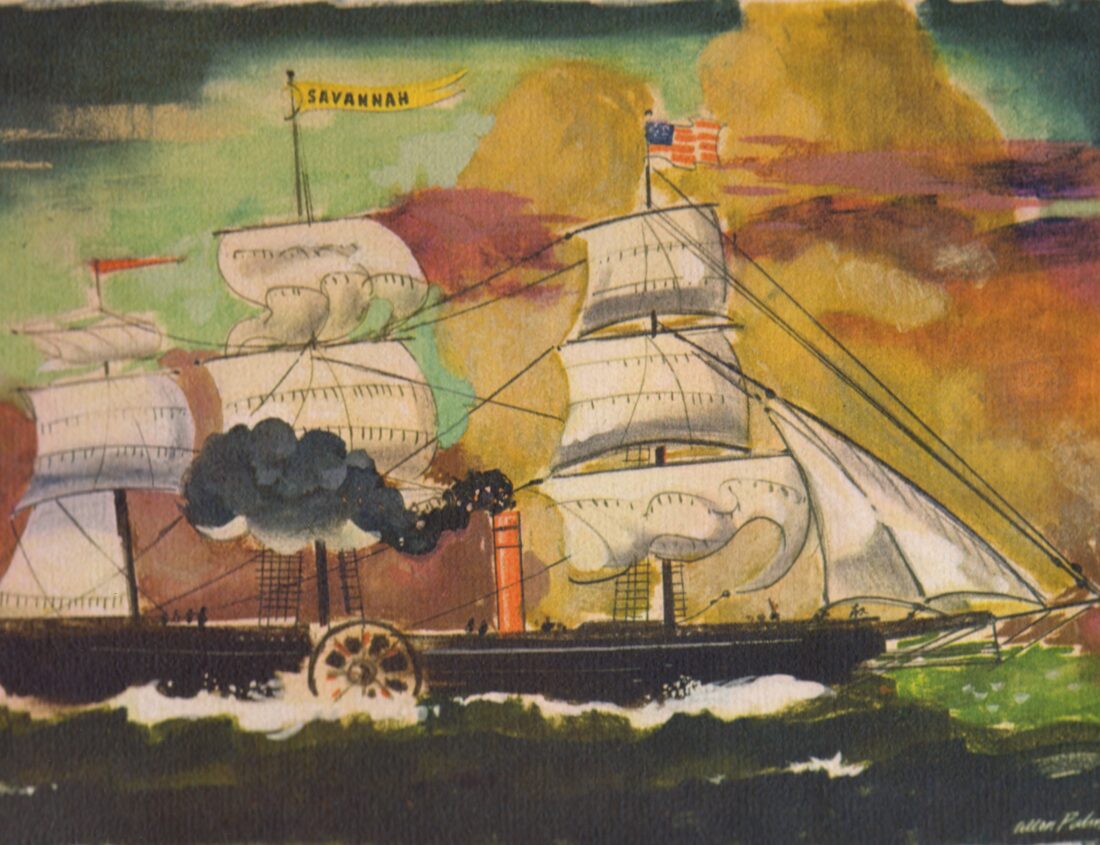

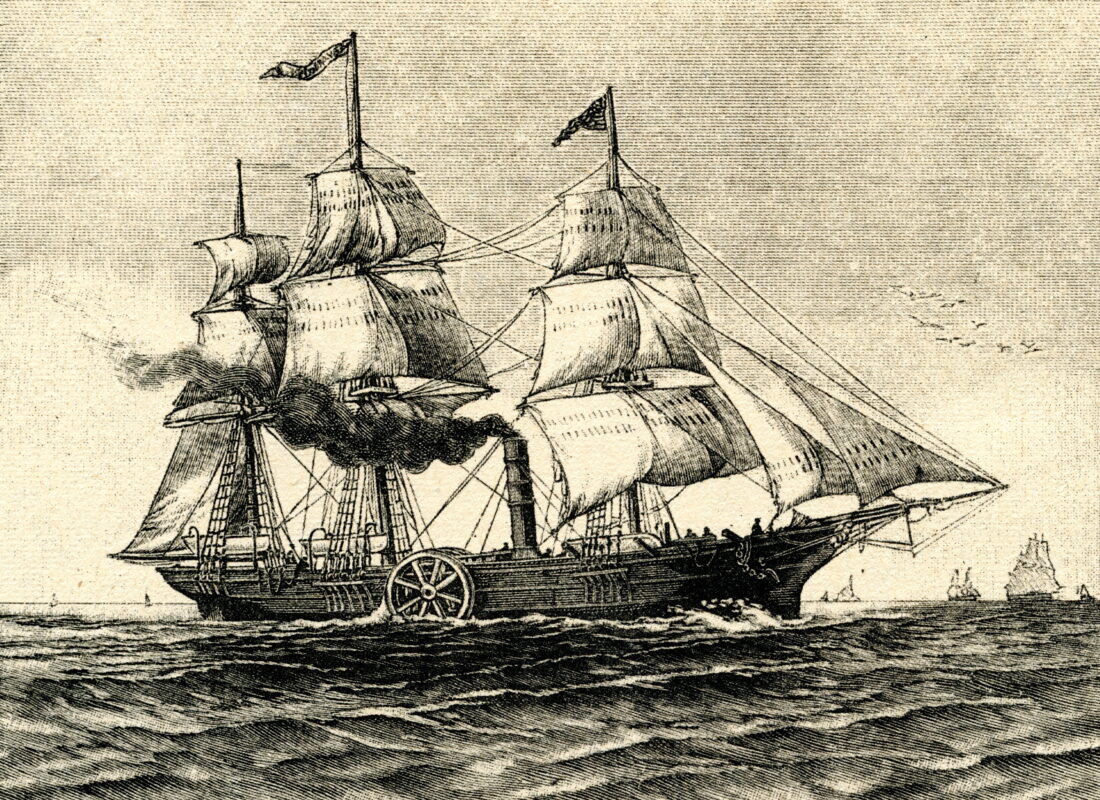

S.S. Savannah, a watercolor by Allan Palmer.

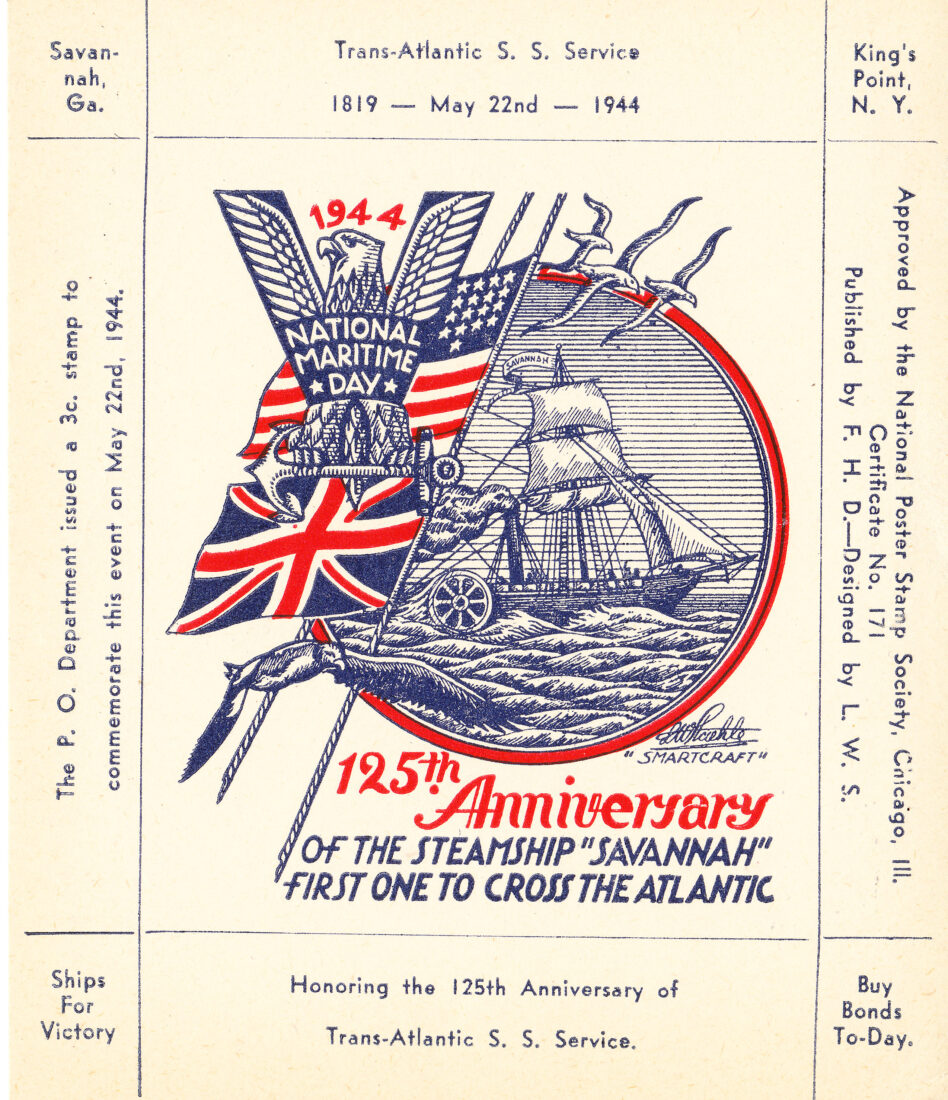

For two centuries, the Georgia-owned SS Savannah, proudly named for its home port, has been something of an archaeological Holy Grail in New York waters. Its wreckage off Fire Island has been sought by scientists and salvagers alike since the ship ran aground off the island in a blow on November 5, 1821, after its benighted captain, then a Mr. Holdredge, had missed the turn into New York harbor at Sandy Hook with his cargo of northbound cotton. Holdredge and his crew managed to get the passengers ashore and salvage the all-important cotton, but the Savannah broke up and has, in shipping parlance, been seeing other duty in Davy Jones’s locker.

William Scarbrough.

It’s hard to overstate the Savannah’s importance to American and European maritime history. Its hard-driving sea-merchant owner, William Scarbrough, a prominent Savannah citizen whose capacious townhouse there now houses the Ships of the Sea Maritime Museum, was a bold, high-tech innovator in his day, and the Savannah was his crowning prize. In shipbuilding parlance, the hundred-foot Havre-style packet was “laid down”—designed and built—in 1818 as one of the world’s first hybrid sail-and-steam-powered merchant ships. Built at the Fickett & Crockett shipyard in Lower Manhattan by the finest early Steam Age craftsmen, the square rigger had just one great piston and cylinder driven by its coal-powered steam engine, which in turn powered a pair of light, innovative, fully retractable sidewheels.

The crew could disassemble and stow the wheels within minutes to reduce drag when under sail power. The engine and its formidable, slanted stack were fitted into the bowels of the boat between the foremast and mainmast. For its day and for its large oceangoing scale—especially considering Robert Fulton had invented the steamboat only eleven years prior—the Savannah was a world-beating Industrial Age engineering feat.

The Museum’s model of the Savannah.

Scarbrough commissioned the talented Connecticut merchant marine cousins of Stevens Rogers and Moses Rogers as the Savannah’s chief outfitters. Stevens supervised much of the innovative design and was the boat’s sailing master; his cousin Moses was Scarbrough’s go-to captain. In 1820, as had been Scarbrough’s plan when he financed the boat, he dispatched Moses to skipper the Savannah’s first and greatest voyage, under sail and steam, across the Atlantic bound for England.

Stevens’s log of that voyage—the world’s first ocean crossing powered in part by steam—now lies in the hands of the Smithsonian. From that record comes the tale: So rare was the sight of the Savannah that, as it neared landfall under full steam off the coast of Ireland, the Irish coast guard down in Cork mistook the furled sails and the great volume of smoke from the stack for a deadly onboard fire and scrambled their rescue cutter, the Kite, out to collect survivors and fight the blaze.

No European sailor had known, much less sailed aboard, an oceangoing steamer before, because there had never been one. The immediate and mysterious problem for the coast guardsmen was that the Kite was not fast enough to overtake the Savannah, so they were forced to fire a warning shot. Captain Moses stopped his ship and congenially invited the flummoxed Irishmen to tie up and come aboard for a tour. That was the unceremonious dawn of mechanized transoceanic crossings then: a ship outbound from Georgia lashed to a cutter off Cork, a boarding party of confused Irishmen milling around on deck, and a giant steam engine idling its five-foot-long piston below.

As a result of its seamless crossing, the Savannah’s intense renown preceded it at literally every European port of call. After refueling and offloading at Liverpool—where the curious thronged the boat daily—the ship docked in Denmark and then Sweden, where the government offered to purchase the ship. Deeming the offer low, Moses refused it because they proposed an exchange of raw goods, not cash.

After sailing across the Baltic to St. Petersburg, Tsar Alexander I’s representatives upped the ante, offering Moses the cash equivalent of a hundred thousand dollars for the boat, his own services, and the crew. Again, the captain turned it down: The Tsar’s plan for the Savannah had been to use it to as a law enforcement frigate for the crown, requiring Moses and the entire crew to stay and work, indentured in all but name to the Russian government.

Back home in Savannah in 1821, things weren’t going brightly for the ship’s bold owner, Scarbrough, who—helped along by the drain of the Savannah, whose world-changing voyage was an utter financial failure—suffered a monetary and emotional collapse, to the point that he had to sell his grand home on what was then West Broad Street to a cousin. Such are the vagaries of fortune among the innovators. He died well known but poor in Savannah in 1838, not living quite long enough to witness the global impact of the transoceanic Steam Age that he daringly fostered.

A stamp commemorating National Maritime Day.

The saga’s final irony is that Scarbrough’s Savannah began to make money only after the steam engine had been removed and the boat had been downgraded to an old-school sailing packet—until then, nobody wanted to ride in or put cargo on a boat with a fire already aboard, however reportedly secure the management. And that fear lay at the bottom of the reason that Scarbrough went broke; his prize boat sailed from Savannah to Liverpool and the Baltic roundly celebrated, but empty of cargo and with no passengers but the crew.

After her world-beating accomplishment under steam, it was in that humble, wind-powered guise that the Savannah met her end off Fire Island. By the end of that century, enormous fleets of transatlantic ocean liners were plying between America and Europe with abandon, like so many pods of great whales. Scarbrough, the broken Georgian, had somehow dreamt it all, but his fate was to realize it far too soon.