Trial and error in the kitchen is a good thing, but you don’t always need to work your way through an entire recipe to determine whether it sucks. As we’re well aware, just because something exists on the internet doesn’t mean an actual authority wrote it. So how does one sort out the frauds from the professionals to minimize cooking risk? You can, in fact, use context clues to skip out on simply bad recipes and prevent certain kitchen disasters.

Every recipe found online should be met with some level of skepticism. Sure, your double chocolate bundt cake looks great, recipe blogger, but guess what, pal? I don’t fucking know you. By agreeing to cook your food, I’m signing off hours of my time and a sizable chunk of money, all because some stranger with incredible self-esteem (hey, good for you) felt the world should no longer be robbed of their turkey pot pie. Nah, whenever I read a recipe online, I ask myself, “Is it possible these chocolate chip cookies are a prank?” and “Who would benefit from seeing me make a bad blueberry pie?” Some might call this paranoia, but a healthy mistrust of the greater recipe community ultimately saves me both time and effort.

As someone who has published a few dozen recipes online, I can tell you what I’ve learned. I can tell you the mistakes I’ve made, and how I know what to trust when I’m scanning the web for dinner ideas. As Los Angeles Times recipe developer Ben Mims once wrote, “Above all, recipes should be instructional and written with an emphasis on clarity.”

With that in mind, when is a recipe not very clear? Look out for the following red flags.

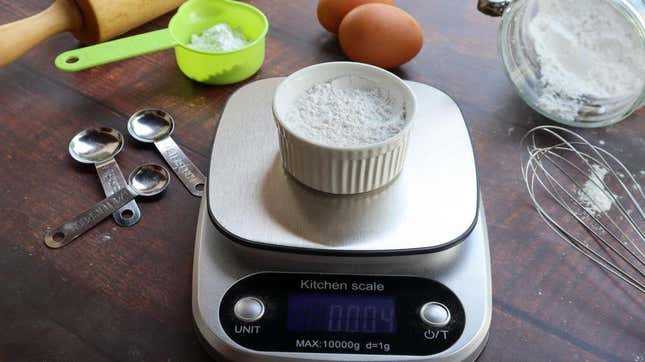

I’m simply done with cup measurements. Give me exact grams or I’m out. There are just too many variables when flour is measured by volume; one cup of flour can actually be a wildly different amount each time you scoop it out of the bag. And when it comes to baking (which I’m bad at), I can’t afford any room for error. A kitchen scale is the only way to get a consistent measurement of flour.

I keep reading that flour changes weight over time based on temperature and humidity, so that’s one variable. Also, Ben wrote about the surprisingly convoluted nature of weighing flour, and how each online publication considers a “cup” of flour to be a different equivalent weight. Check it out:

King Arthur Flour: 120 grams

Bake From Scratch: 125 grams

Washington Post: 126 grams

The New York Times: 128 grams

Bon Appétit: 130 grams

AllRecipes.com: 136 grams

The L.A. Times; Cook’s Illustrated: 142 grams

Does any of this matter? Well, if you’re measuring these brands of flour by cups, hell yes it does. More flour means your pie crust is going to be drier and flakier. More flour means you’ll have to add more liquid to your pasta dough, and it’ll be a huge pain in the ass to knead. I actually don’t need science to tell me this, either; I know from personal experience that when I weigh flour for pasta by the cup, I will occasionally run into a problem. Why? It’s not exact.

I have never had a problem with semolina pasta dough since I started measuring it in grams and milliliters. By the way, that is 255 grams of semolina flour to 150 ml of warm water. Knead for 10 minutes. Works every time. A digital scale has made my life infinitely easier when working with finicky things like dough. Get a digital scale for like $10-$40 at Target or on Amazon.

This is hugely important, especially if you’re not getting your recipe from a single trusted source like, say, Ben Mims or J. Kenji López-Alt.

Professional websites like The Kitchn have cross testers, and so when I write a recipe for that publication, I feel supremely confident that the recipe works. Cross testers take the recipe’s copy and stick to it pretty literally, since that’s how the reader’s going to take it, too. Not only does the cross tester check to see if the recipe tastes good, but they’re also analyzing the instructions for clarity.

In addition to a cross tester, The Kitchn also has an editor. Next, the food gets shoved off to a food stylist. That’s four people involved in the process of publishing my recipe. That collaboration is super rad, and it makes an already excellent recipe that much more airtight.

In the aforementioned Ben Mims article, he suggests that your average person doesn’t really stop to consider the source of the recipe itself. “New cooks just want a recipe, period, and they don’t really care if it’s tested well or comes from a trusted source,” he writes.

I’ll say it: You should absolutely give a shit about the source your recipe is coming from. Use trusted websites, and trust collaborative efforts.

I’m serious here. Look for the word “meanwhile” in a recipe. Why? “Meanwhile” implies multitasking, and multitasking means that the professionals writing this recipe value your time.

Nobody has time to cook all day. When I submit a recipe, the editor often asks if there’s a way to consolidate steps, or they inquire if there’s a way to make the cooking process faster. Recipes are written in a linear fashion, often to a fault, and so they can often read like a run-on sentence: “and then… and then… and then…”

“Meanwhile” is how real cooking happens, juggling simultaneous tasks to save time. To me, this word signifies that the recipe has been tested by folks who have a keen understanding that you’re trying to put dinner on the table.

For the love of god, a recipe should be easy to read. There should be headers. There should be adequate spaces in between sentences and paragraphs. When the recipe publication itself looks rushed, guess what? The recipe is also probably rushed. It’s got to be easy to read and to navigate. If it doesn’t, I’m out. And you should be, too.

Recipe websites with a ton of scrolling? Get out. Broken links? Pictures that aren’t resized? Buddy, that’s a blog, and blogs can only be trusted on a case by case basis. An overabundance of buttons, links, and branding are all reasons to be on high alert. There’s a chance these recipes weren’t written for your benefit in the slightest.

You know, everybody gets up in arms about the text that comes before a recipe. Sometimes that headnote is a personal story; sometimes it’s a series of technical anecdotes about the dish itself. Me? I love these things, and I read them in full. I also use this as a chance to appraise the cook writing the recipe. If the writing looks like it was handled with care and went through a solid round of editing, there’s a good chance the cook has invested a similar amount of time making the recipe work. If the copy before the recipe is just full of search-engine-optimizing keywords (“I like chocolate chip cookies I made cookies and everybody loves these chocolate chip cookies”), then I’m out. Clarity is most important, but some compelling, thoughtful writing never hurts.